Silence, sexism and stigma: The state of working-age women’s health in England

Multiple reports, including most recently from the House of Commons women and equalities committee on women’s reproductive health conditions, highlight that medical symptoms experienced by women consistently get dismissed. Experiences of pain become normalised, and there is a pervasive stigma associated with gynaecological health.

On average, women spend more of their lives in poor health through illness or disability than men. Over the decade between 2011 and the most recent data in 2021, this gap has remained unchanged. It’s commonly assumed that this health burden is concentrated in older age because women live longer, but women actually spend more time living in ill health throughout their working years. Long-term illness is the most common reason for working-aged women being economically inactive, and sickness absence levels are almost two days per year higher in women than in men.

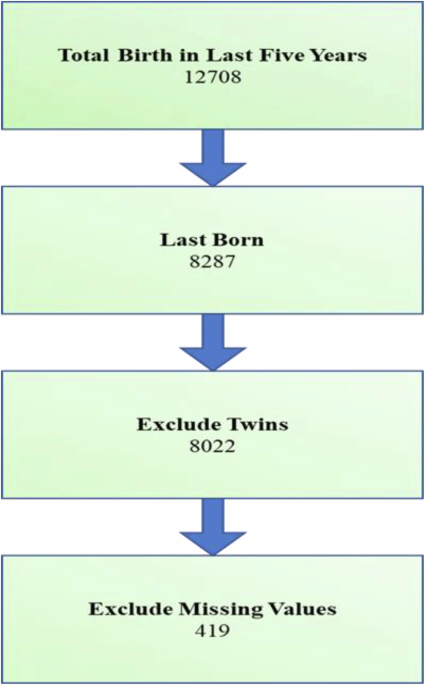

This analysis looks at the health challenges faced by women

of working age in England, understood here as a broad age range from 15 to 69 years old. We draw on data from the most recent Global Burden of Disease study, and also from the Hospital Episode Statistics inpatient dataset. While the economic effects of women living in poor health are clear, ensuring women are supported to thrive at working age is important for reasons beyond the economy: good health is a necessary condition for women to exercise choice over whether and how they participate in the workforce, both formal and informal.

Let’s begin by understanding the burden of disease on working-age women. A good way of measuring the overall burden of disease is through disability-adjusted life years (DALYs).

While the burden of disease from some conditions reduced over the decade between 2011 and 2021, there was an overall increase of healthy years of life lost for working-age adults, especially for women. Without accounting for the impact of Covid-19

, the percentage increase in DALYs lost to all conditions between 2011 and 2021 was 4% for women aged 15 to 69, compared to 1% for men of the same age group. This may be driven by differing trends in disease burden, access to care, or exposure to risk factors.

Let’s look in more detail at the 15 conditions that most affected both women and men of working age as of 2021…

In 13 out of the top 15 conditions affecting both working-age women and men in 2021, the percentage reduction in DALYs since 2011 was either lower for women than it was for men, or DALYs had actually increased for women since 2011, with better progress for men. In England, working-age women lost a total of 139,019 more years of healthy life than men. Even as health burdens for specific conditions such as lung cancers and ischemic heart disease have reduced in the last decade across the population, working-age women have not benefited equally.

Over the same time period, the biggest difference in changing health burdens for a specific condition was for opioid use disorders, where there was a 37% increase in DALYs for women between 2011 and 2021. The percentage increase for men was much lower, at 12%. Overprescribing of opioids – particularly for chronic pain – may partly explain this disproportionate increase for women.

Overall, DALYs in women have either increased or there has been slower progress in reducing DALYs for women in conditions that also affect men. But this is just one part of a broader picture. Looking at a set of specific conditions that affect women and men differently, we can see some notable characteristics.

Exploring the absolute difference in DALYs between working-age women and men highlights different health needs between the sexes, and points to how best to support the workforce. In 2021, the conditions that working-age women lost the most healthy life years to (as compared to men) were gynaecological conditions and breast cancer. Mental health disorders such as major depressive disorder, anxiety disorder and bipolar disorder also place a heavier burden on working-age women. In contrast, conditions that affect men differently carry a higher premature mortality burden, such as Covid-19

or heart disease. Next, we’ll look at some of the conditions and types of services that are most closely linked to these disparities.

Breast cancer

Breast cancer predominantly affects women. As of 2021, most occurrences of breast cancer in women (65%) happen during working-age years, with the highest incidence for women aged between 50 and 69 years old. Breast screening – which can detect early-stage cancers often associated with better treatment outcomes – is an important route to diagnosis. While the number of women attending screening increased by 5% between 2022/23 and 2023/24, there is still a significant need to increase screening rates, as 30% of women invited to screening did not attend. Treatment for breast cancer can involve a mix of surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy, with patients often needing to be off work for extended periods of time to receive care.

Gynaecological services

Between April 2011 and April 2025 (the latest available data at the time of writing), the gynaecology specialty waiting list grew by 275%, compared to an average 199% increase in waiting list size across all specialties. This is leaving thousands of women waiting for essential procedures and tests, and can lead to delayed diagnosis. As of April 2025, 580,010 women were waiting over 18 weeks for their first consultant-led care.

One area particularly emblematic of these failures is the treatment and management of endometriosis. Endometriosis, an often painful condition where tissue similar to the lining of the uterus grows outside of the uterus, affects approximatively 1 in 10 women in the UK. On average, the time between the first GP visit and receiving a diagnosis is 8 years and 10 months. Women waiting for a diagnosis can be left managing the debilitating impact of pain on their day-to-day lives, and may resort to accessing emergency health care services.

“No woman says she is in pain unless she is in real pain. No woman says she is anxious unless she is really anxious. No woman wants to appear weak or appear incapable until she really is, until she cannot cope any more, and it should not be that way”

Naga Munchetty, Women and Equalities Committee

Tackling rising economic inactivity due to ill health is a priority for the government. Our analysis of disability-adjusted life years over the last decade for which data is available shows that working-age women have seen a faster growth in health burdens than working-age men, and women spend more of their working years living in ill health.

Investing in the health of working-age women generates broader social and economic benefits, as well as enhancing the wellbeing of individuals: each additional £1 spent per woman on obstetrics and gynaecology services throughout the NHS is estimated to generate a return of around £11.

The disproportionate burden of working-age ill health on women is in some ways unsurprising. Gynaecological conditions often present at working age, and breast cancer (predominantly a disease affecting women) tends to develop at a younger age than male-specific cancers such as prostate cancer. Conditions with a high disability burden and pain-driven conditions – many of which remain largely invisible (e.g. musculoskeletal conditions and mental ill-health) – take a disproportionate toll on working-age women. Improving the speed at which women can access diagnosis and treatment for these conditions is key to reducing the disease burden carried by working-age women. But the increasing waiting list for gynaecology services, declining uptake of breast cancer screening and high emergency hospitalisation rate for working-age women all suggest there is much to be done.

Improving working-age women’s health will also require more research considering how the intersectional effects of age, sex, disability, economic status and ethnicity affect ill-health, as well as access to and benefit from health care. Better public availability of sex-specific and gender identity-specific data is also vital: the current lack of data could lead to underestimation of disease burden and contribute to disparities in diagnosis, treatment decisions, or access to appropriate care for different patient groups.

A government focused on reducing economic inactivity from ill health should see much to be gained by investing in better health care for women. But alongside investment in ‘resources’ like staff and scanners sits the even harder job of changing culture. For too long, sexism and ‘medical misogyny’ have persisted in the NHS, normalising and dismissing conditions predominantly affecting women.

Until that changes, progress is likely to be limited.

link